|

hun eng |

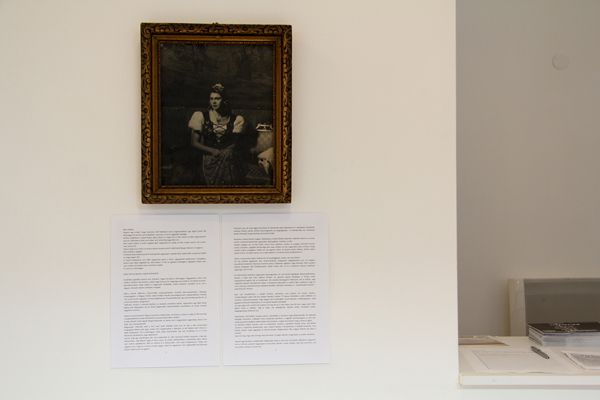

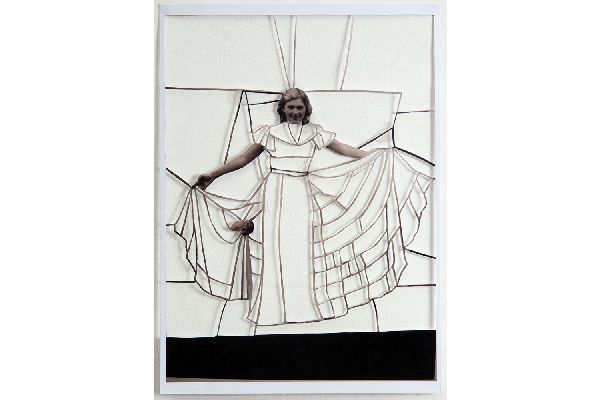

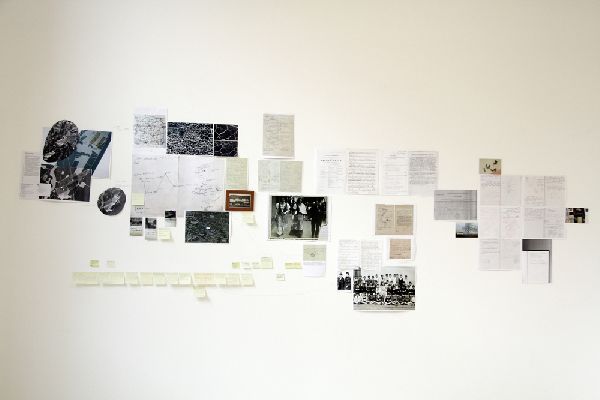

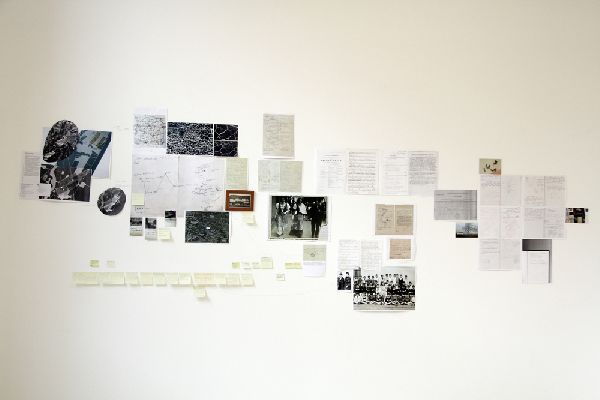

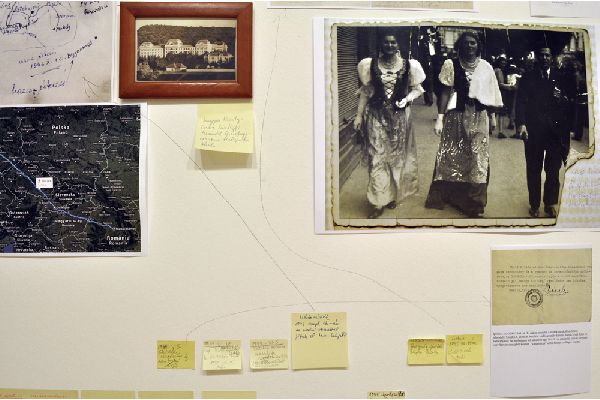

The Objects Found Me In February of 2014, I received a photo in an email. The sender, the art historian Dr Ferenc Matits, asked me if I knew a pianist by the name of Mrs Miklós Chilf, because the ceremonial gala costume worn by the woman in the photograph had belonged to her. I searched for the black and white photograph of Mária Chilf, my grandmother on my father's side, which had been preserved since my childhood. In the photograph I saw the same dress. I didn't know much about my grandmother, who had died relatively young, although according to my mother (who also never met her) I resemble her. In my childhood, I had often looked at the photo of my queenly, fairy tale-like grandmother, and I had wished objects could talk. There are three objects in the photograph and I have come to possess all three of them. Two of them have been to Bergen-Belsen. My grandmother's second husband sent me, by way of my mother, the crescent-shaped white-gold diamond Turkish ring, of which he declared that I was the rightful owner. I had seen the jacquard tapestry in front of which my grandmother poses in the photograph in my grandfather’s Biedermeier room, which I was only rarely allowed to enter. It is the single valuable property I had inherited from my grandparents. And now this gala costume.

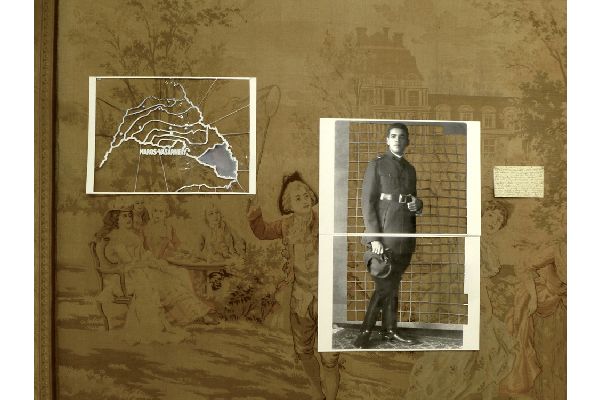

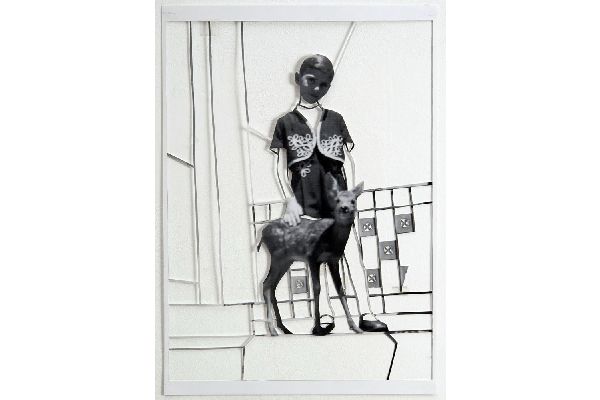

Márta Husztfalvi took care of the woman's Hungarian gala costume for seventy years and then gave it to the Hungarian National Museum on a long-term loan. We met Márta in Balassagyarmat at her daughter’s place. The photograph depicts her. Márta’s family had arrived in Marosvásárhely (now Târgu Mure? in Romania) in 1940, when Transylvania was re-annexed to Hungary. As a sub-lieutenant, her father, László Husztfalvi, was the steward of the Prince Csaba Hungarian Royal Rapid Corps Military Academy. As an inmate of a labour camp, my Jewish grandfather, Miklós Chilf, was placed under him. The sub-lieutenant and my grandfather, who was a renowned pianist, became friends, and my grandfather was able therefore – as an inmate – to garden and play the piano in the officer's club.

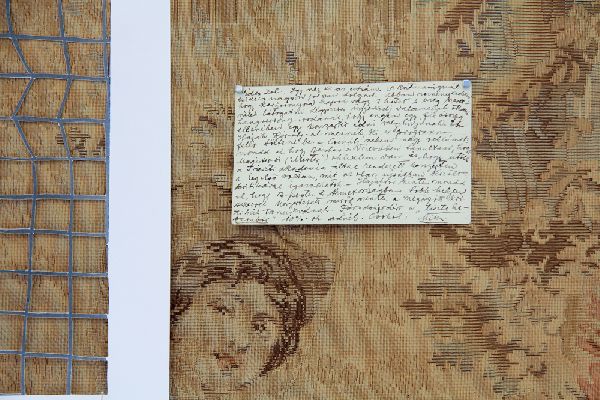

In 1944, when the Soviets reached the Romanian border and Romania successfully pulled out of its alliance with Germany, the military academy had to be moved. It was at this time that my grandparents entrusted Márta’s father, who was responsible for transporting the academy’s weapons, tanks and equipment, with a chest. They left Marosvásárhely with the last train. The chest, the contents of which were written down in a handwritten list, had to be delivered to relatives living in Hungary. According to the inventory, the chest contained my grandmother’s gala costume and the wall tapestry. En route, on October 7th, 1944, the train was bombed in Érsekújvár (now Nové Zámky in Slovakia). In the dreadful bombing Márta lost her brother and almost all of the family’s possessions. Only a few pieces of furniture and my grandmother’s chest survived.

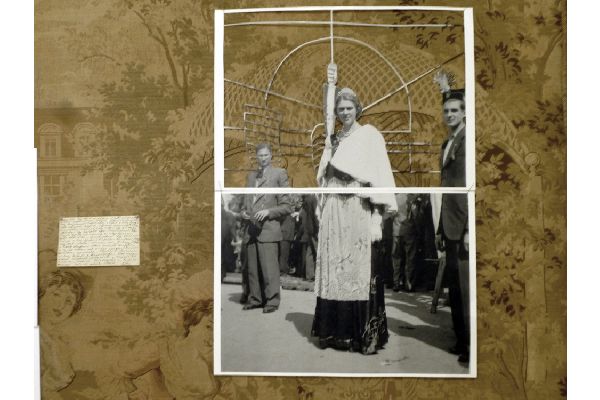

Márta’s family and some of the pupils and instructors of the military academy were imprisoned in the Bergen-Belsen military camp. My grandparent’s chest was with them. After the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, László Husztfalvi helped survivors of the camp with the items that had been in the chest. A grateful survivor of the camp, Gyula Perl, brought the chest and its contents to Budapest in 1945 and gave it to my grandmother. My grandmother, who in the meantime had also arrived back home, gave the gala costume to the 17-year old Márta as a gift, telling her to have it altered, since one would not have been able to wear it as it was in Romania. The dress was never altered, however, but hung in the closet for seventy years. It was taken from here and placed in the storage facilities of the museum. It was from the museum that I took it as something that now belonged to me.

I brought it home in the evening, but only unpacked it the next morning. Acid free paper separated the individual pieces (bodice, skirt, apron headdress). When I unpacked it I smelled it… Clothes have souls. It had been embroidered by hand and safely kept for generations. There are many experiences one has because of odours for which I have no words. When you come into contact with something through the palpable material. It connects. A smell at least 74 years old, which included my grandmother’s smell, as if the object could talk. The material had survived the person who once had held it, and it had come to be in the possession of someone else. And my own death is in it as well. If there were someone to whom I could give it to, could I? I untangled the threads of the story, letting things happen on their own. I would not have been capable of taking everything in immediately anyway. It was an internal process, which is hard to hand over, like a smell.

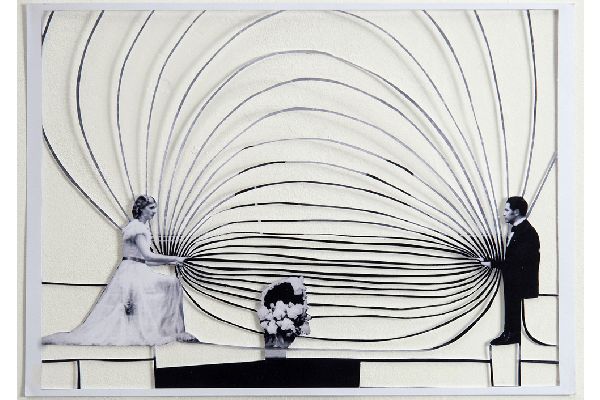

In the photograph I received from my father my Christian-born Catholic grandmother is seen wearing this gala costume at a reception for Horthy in Marosvásárhely, together with my grandfather, who converted to Christianity in 1939. Later I found the news reel from 1940 entitled Kelet felé (Towards the East), and I thought I recognized my grandmother in a couple of its frames. My father began talking about the history of the family two years ago. At 77 years of age he acknowledged that some of his ancestors were Jewish, and he showed my documents about my great-grandfather, who given the circumstances in which he lived spoke five languages, left Lemberg to study in Vienna, and became the director of a college in Marosvásárhely.

There is a past of which I had no knowledge, the strands of which I am hesitant to join, for who knows where they might lead. My grandfather was considered a man of renown in Transylvania. He owned the best concert piano. In Marosvásárhely everyone knew me as the grandchild of Miklós Chilf. On Sundays, we had to go to their home for lunch. I couldn’t stand the smell, and even the silence hummed. I now received a piece of my family. I learned of something for which I had not been searching. About others, about myself. I resemble the grandmother born 100 years ago, whose name I bear, but whom I never knew.

Mária Chilf

|

|